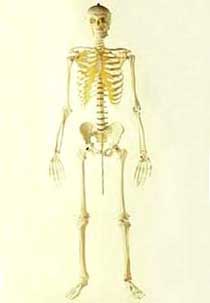

DK Human Body: Skeleton

The skeleton is the inner framework of BONES that supports and gives shape to the human body. It also protects some of the soft organs of the body—for example, the skull surrounds the brain. Muscles and ligaments pull on the bones of the skeleton at JOINTS to make the body move.

Each bone in the body has a scientific name, but many also have everyday names. The largest is the femur, or thighbone, and the smallest are the tiny ossicle bones in the inner ear. More than half the bones of an adult’s skeleton are in the hands and feet.

Weight for weight, bone is five times stronger than steel, but it is very light. The skeleton makes up only one-sixth of an adult’s weight. The skull, in particular, is very strong, because it has to protect the brain and sense organs, such as the eyes, ears, and nose.

Dead bones are dry and brittle, but living bones feel wet and a little soft. They are also slightly flexible, so they can absorb pressure. Like most parts of the body, bones have a network of blood vessels and nerves running through them, and they bleed when broken. Up to one-third of the weight of a living bone is water.

A newborn baby has more than 300 bones, but many are made of a soft, rubbery material called cartilage instead of bone. Up until the late teens, as a child grows the cartilage lengthens and turns into bone, and some bones fuse together. By adulthood, there are just 206 bones in the skeleton.

This strong yet flexible material is a living tissue, made up of bone cells embedded in a matrix of fibers. Bone is not solid—blood vessels and nerves run through tunnels within it, and some areas are a honeycomb of small spaces. In the center of many bones is a cavity packed with a jellylike substance called bone marrow.

The hard matrix of bone is made of crystals of calcium phosphate and other minerals, and fibers of protein called collagen. The minerals make bone hard, while the collagen fibers are arranged lengthwise to make bone flexible. Both are produced by cells called osteocytes, found throughout the matrix.

Bone marrow makes millions of blood cells every second to replace old, worn-out blood cells, which the body destroys. There are two types of marrow: red and yellow. Red marrow makes blood cells. Yellow marrow is mainly a fat store, but it can turn into red marrow if the body needs extra blood cells. At birth, nearly all bone marrow is red. During the teens, much of it turns into yellow bone marrow.

Bones connect at joints. Different types of joint allow different movements. Joints are often held together by straps of tough fibrous tissue, called ligaments, and the muscles that cross the joint.

Most joints are free-moving. These are called synovial joints, and they allow varying degrees of movement. Hinge joints, like those in the fingers, knees, and elbows, can only bend and straighten. Others, such as the ball-and-socket joints in the shoulders and hips, allow movement in all directions.

In synovial joints, the bone endings are covered with a smooth, glossy material called hyaline cartilage, which is slippery yet hard-wearing. This cartilage allows the bone ends to slide smoothly past each other. Also, a capsule of fluid surrounds the joint. The fluid lubricates the joint, reducing friction just as oil helps the movement of a bicycle chain.